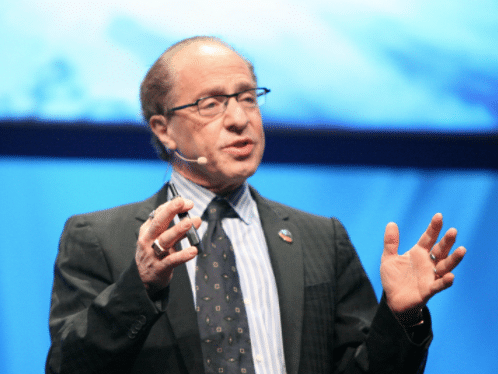

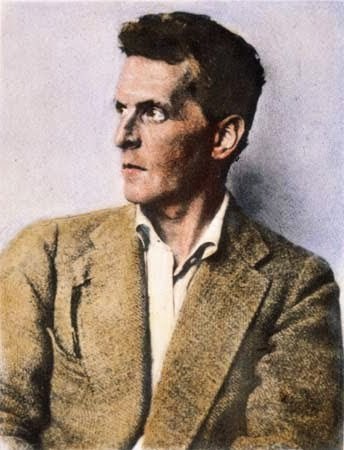

I made an introductory talk on word embeddings in the past and this write-up is an extended version of the part about philosophical ideas behind word vectors. The aim of this article is to provide an introduction to Ludwig Wittgenstein’s main ideas on linguistics that are closely related to techniques that are distributional (I’ll talk what this means later) by design, such as word2vec [Mikolov et al., 2013], GloVe [Pennington et al., 2014], Skip-Thought Vectors [Kiros et al., 2015], among others.

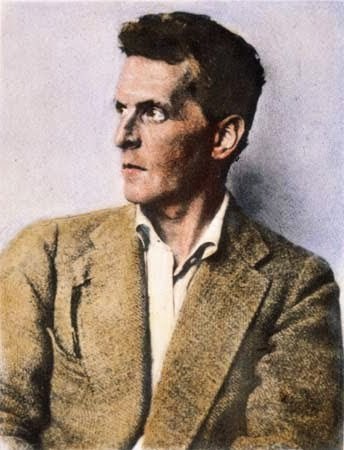

One of the most interesting aspects of Wittgenstein is perhaps that fact that he had developed two very different philosophies during his life, and each of which had great influence. Something quite rare for someone who spent so much time working on these ideas and retreating even after the major influence they exerted, especially in the Vienna Circle. A true lesson of intellectual honesty, and in my opinion, one important legacy.

One of the most interesting aspects of Wittgenstein is perhaps that fact that he had developed two very different philosophies during his life, and each of which had great influence. Something quite rare for someone who spent so much time working on these ideas and retreating even after the major influence they exerted, especially in the Vienna Circle. A true lesson of intellectual honesty, and in my opinion, one important legacy.

Wittgenstein was an avid reader of the Schopenhauer’s philosophy, and in the same way that Schopenhauer inherited his philosophy from Kant, especially regarding the division of what can be experimented (phenomena) or not (noumena), contrasting things as they appear for us from things as they are in themselves, Wittgenstein concluded that Schopenhauer philosophy was fundamentally right. He believed that in the noumena realm, we have no conceptual understanding and therefore we will never be able to say anything (without becoming nonsense), in contrast to the phenomena realm of our experience, where we can indeed talk about and try to understand. By adding secure foundations, such as logic, to the phenomenal world, he was able to reason about how the world is describable by language and thus mapping what are the limits of how and what can be expressed in language or in conceptual thought.

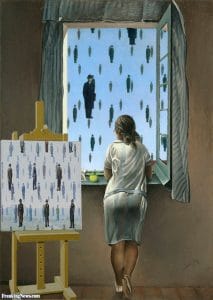

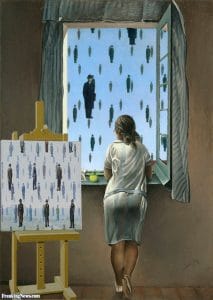

The first main theory of language from Wittgenstein, described in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, is known as the “Picture theory of language” (aka Picture theory of meaning). This theory is based on an analogy with painting, where Wittgenstein realized that a painting is something very different than a natural landscape, however, a skilled painter can still represent the real landscape by placing patches or strokes corresponding to the natural landscape reality. Wittgenstein gave the name “logical form” to this set of relationships between the painting and the natural landscape. This logical form, the set of internal relationships common to both representations, is why the painter was able to represent reality because the logical form was the same in both representations (here I call both as “representations” to be coherent with Schopenhauer and Kant terms because the reality is also a representation for us, to distinguish between it and the thing-in-itself).

This theory was important, especially in our context (NLP), because Wittgenstein realized that the same thing happens with language. We are able to assemble words in sentences to match the same logical form of what we want to describe. The logical form was the core idea that made us able to talk about the world. However, later Wittgenstein realized that he had just picked a single task, out of the vast amount of tasks that language can perform and created a whole theory of meaning around it.

The fact is, language can do many other tasks besides representing (picturing) the reality. With language, as Wittgenstein noticed, we can give orders, and we can’t say that this is a picture of something. Soon as he realized these counter-examples, Wittgenstein abandoned the picture theory of language and adopted a much more powerful metaphor of a tool. And here we’re approaching the modern view of the meaning in language as well as the main foundational idea behind many modern Machine Learning techniques for word/sentence representations that works quite well. Once you realize that language works as a tool, if you want to understand the meaning of it, you just need to understand all the possible things you can do with it. And if you take for instance a word or concept in isolation, the meaning of it is the sum of all its uses, and this meaning is fluid and can have many different faces. This important thought can be summarized in the well-known quote below:

The meaning of a word is its use in the language.

(…)

One cannot guess how a word functions. One has to look at its use, and learn from that.

– Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

And indeed it makes complete sense because once you exhaust all the uses of a word, there is nothing left on it. Reality is also by far more fluid than usually thought, because:

Our language can be seen as an ancient city: a maze of little streets and squares, of old and new houses, and of houses with additions from various periods (…)

– Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

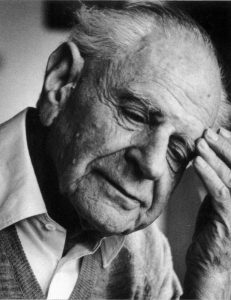

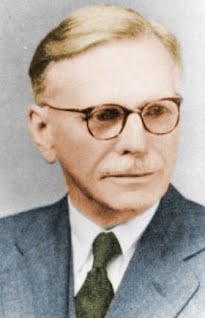

John R. Firth was a linguist also known for the popularization of this context-dependent nature of the meaning who also used Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations as a recourse to emphasize the importance of the context in meaning, in which I quote below:

John R. Firth was a linguist also known for the popularization of this context-dependent nature of the meaning who also used Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations as a recourse to emphasize the importance of the context in meaning, in which I quote below:

The placing of a text as a constituent in a context of situation contributes to the statement of meaning since situations are set up to recognize use. As Wittgenstein says, ‘the meaning of words lies in their use.’ (Phil. Investigations, 80, 109). The day-to-day practice of playing language games recognizes customs and rules. It follows that a text in such established usage may contain sentences such as ‘Don’t be such an ass !’, ‘You silly ass !’, ‘What an ass he is !’ In these examples, the word ass is in familiar and habitual company, commonly collocated with you silly-, he is a silly-, don’t be such an-. You shall know a word by the company it keeps ! One of the meanings of ass is its habitual collocation with such other words as those above quoted. Though Wittgenstein was dealing with another problem, he also recognizes the plain face-value, the physiognomy of words. They look at us ! ‘The sentence is composed of words and that is enough’.

– John R. Firth

This idea of learning the meaning of a word by the company it keeps is exactly what word2vec (and other count-based methods based on co-occurrence as well) is doing by means of data and learning on an unsupervised fashion with a supervised task that was by design built to predict context (or vice-versa, depending if you use skip-gram or cbow), which was also a source of inspiration for the Skip-Thought Vectors. Nowadays, this idea is also known as the “Distributional Hypothesis“, which is also being used on fields other than linguistics.

Now, it is quite amazing that if we look at the work by Neelakantan, et al., 2015, called “Efficient Non-parametric Estimation of Multiple Embeddings per Word in Vector Space“, where they mention about an important deficiency in word2vec in which each word type has only one vector representation, you’ll see that this has deep philosophical motivations if we relate it to the Wittgenstein and Firth ideas, because, as Wittgenstein noticed, the meaning of a word is unlikely to wear a single face and word2vec seems to be converging to an approximation of the average meaning of a word instead of capturing the polysemy inherent in language.

A concrete example of the multi-faceted nature of words can be seen in the example of the word “evidence”, where the meaning can be quite different to a historian, a lawyer and a physicist. The hearsay cannot count as evidence in a court while it is many times the only evidence that a historian has, whereas the hearsay doesn’t even arise in physics. Recent works such as ELMo [Peters, Matthew E. et al. 2018], which used different levels of features from a LSTM trained with a language model objective are also a very interesting direction with excellent results towards incorporating a context-dependent semantics into the word representations and breaking the tradition of shallow representations as seen in word2vec.

We’re in an exciting time where it is really amazing to see how many deep philosophical foundations are actually hidden in Machine Learning techniques. It is also very interesting that we’re learning a lot of linguistic lessons from Machine Learning experimentation, that we can see as important means for discovery that is forming an amazing virtuous circle. I think that we have never been self-conscious and concerned with language as in the past years.

I really hope you enjoyed reading this !

– Christian S. Perone

References

Magee, Bryan. The history of philosophy. 1998.

Mikolov, Thomas et al. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. 2013. https://arxiv.org/abs/1301.3781

Pennington, Jeffrey et al. GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation. 2014. https://nlp.stanford.edu/projects/glove/

Kiros, Ryan et al. Skip-Thought Vectors. 2015. https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.06726

Neelakantan, Arvind et al. Efficient Non-parametric Estimation of Multiple Embeddings per Word in Vector Space. 2015. https://arxiv.org/abs/1504.06654

Léon, Jacqueline. Meaning by collocation. The Firthian filiation of Corpus Linguistics. 2007.

One of the most interesting aspects of Wittgenstein is perhaps that fact that he had developed two very different philosophies during his life, and each of which had great influence. Something quite rare for someone who spent so much time working on these ideas and retreating even after the major influence they exerted, especially in the Vienna Circle. A true lesson of intellectual honesty, and in my opinion, one important legacy.

One of the most interesting aspects of Wittgenstein is perhaps that fact that he had developed two very different philosophies during his life, and each of which had great influence. Something quite rare for someone who spent so much time working on these ideas and retreating even after the major influence they exerted, especially in the Vienna Circle. A true lesson of intellectual honesty, and in my opinion, one important legacy.

John R. Firth

John R. Firth