Notes on Gilbert Simondon’s “On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects” and Artificial Intelligence

* This time, this is not a technical article (but it is about philosophy of technology 😄)

This is a short opinion article to share some notes on the book by the French philosopher Gilbert Simondon called “On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects” (Du mode d’existence des objets techniques) from 1958. Despite his significant contributions, Simondon still (and incredibly) remains relatively unknown, and it seems to me that this is partly due to the delayed translation of his works. I realized recently that his philosophy of technology aligns very well with an actionable understanding of AI/ML. His insights illuminated a lot for me on how we should approach modern technology and what cultural and societal changes are needed to view AI as an evolving entity that can be harmonised with human needs. This perspective offers an alternative to the current cultural polarization between technophilia and technophobia, which often leads to alienation and misoneism. I think that this work from 1958 provides more enlightening and actionable insights than many contemporary discussions of AI and machine learning, which often prioritise media attention over public education. Simondon’s book is very dense and it was very difficult to read (I found it more difficult than Heidegger’s work on philosophy of technology), so in my quest to simplify it, I might be guilty of simplism in some cases.

Culture positioning itself as a defensive system against technology

One of the key points that Simondon talks about is regarding how culture sees technology. According to Simondon, culture has constituted itself as a “defense system” against technology. Well, it doesn’t take much effort for us to understand that this seems to be getting worse lately and especially after the post-LLM world in ML, with more and more folks joining the chorus of apocalyptic views. If we look back, however, history shows that this has always been the case with technology. Culture ignores the human reality within the technical reality, it sees it as something artificial that is opposite to the natural world. Simondon says that:

Culture behaves toward the technical object as man toward a stranger, when he allows himself to be carried away by primitive xenophobia. Misoneism directed against machines is not su much a hatred of novelty as it is a rejection of a strange or foreign reality. However, this strange or foreign being is still human, and a complete culture is one which enables us to discover the foreign or strange as human.

– Gilbert Simondon, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects (p10), 1958.

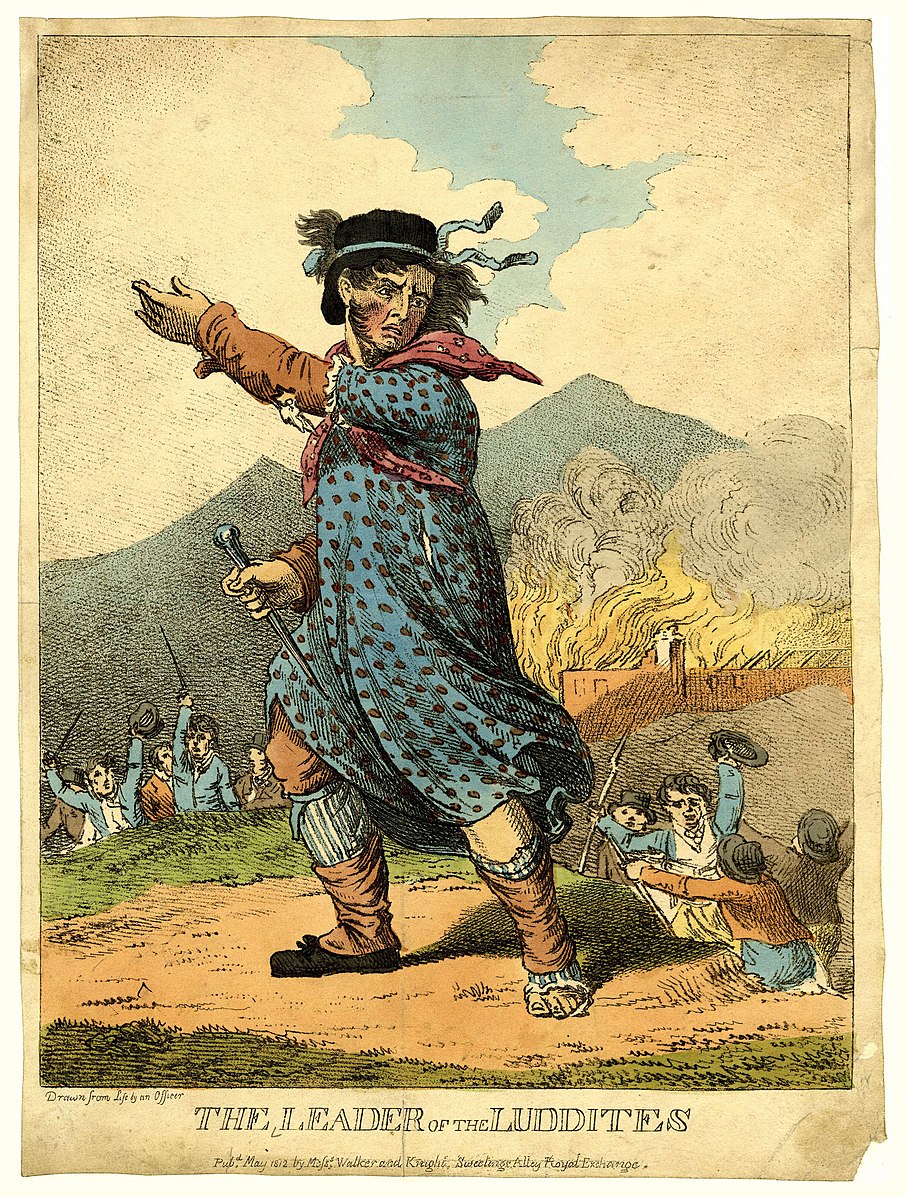

If we look at where we are today, with some people advocating to decelerate data center construction, it resembles the English Luddite movement of the 19th century where workers destroyed textile machinery due to concerns relating to worker pay and output quality. The cause of this, according to Simondon is alienation, and the most powerful cause of alienation is the misunderstanding of the machine and technology, which is not an alienation caused by technology but by the non-knowledge of its nature and its essence. This alienation, inadequate and confused rapport between consumer, manufacturer and worker should be replaced by a awareness of the mode of existence of technical objects, to integrate them back into culture and its values. There are also endless examples of how culture is acting in a defensive way against technology recently, take for example the resistance of use of LLMs in education, it is often seen as fostering diminished critical thinking and threatening the traditional educational values rather than enhancing them. Even Stephen Hawking said that “the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race” in a BBC interview, whatever “full” means.

Culture has turned us blind, it reduced technology to a set of neutral instruments at the service technocratic will, posing as if it is a simple tool with an utility, fostering this polarized view of technology and Artificial Intelligence as either technophilia (uncritical love of AI and technology) or technophobia (fear or rejection of AI and technology). These polarized views end up masking the rich human efforts and natural forces shaping technical objects as mediators between man and nature.

Automatism and the mythical representation of the robot

The defensive rejection of technical objects by culture, as it recognizes certain objects like aesthetic objects but sees technical objects as, according to Simondon, “structureless world of things that have no signification but only a use, a utility function”, makes people who have knowledge of technical objects and that appreciate their signification, to seek justification of their judgment by granting these technical objects a status of sacred and embedded in this mythical idea of the “robot”, as explained by Simondon below:

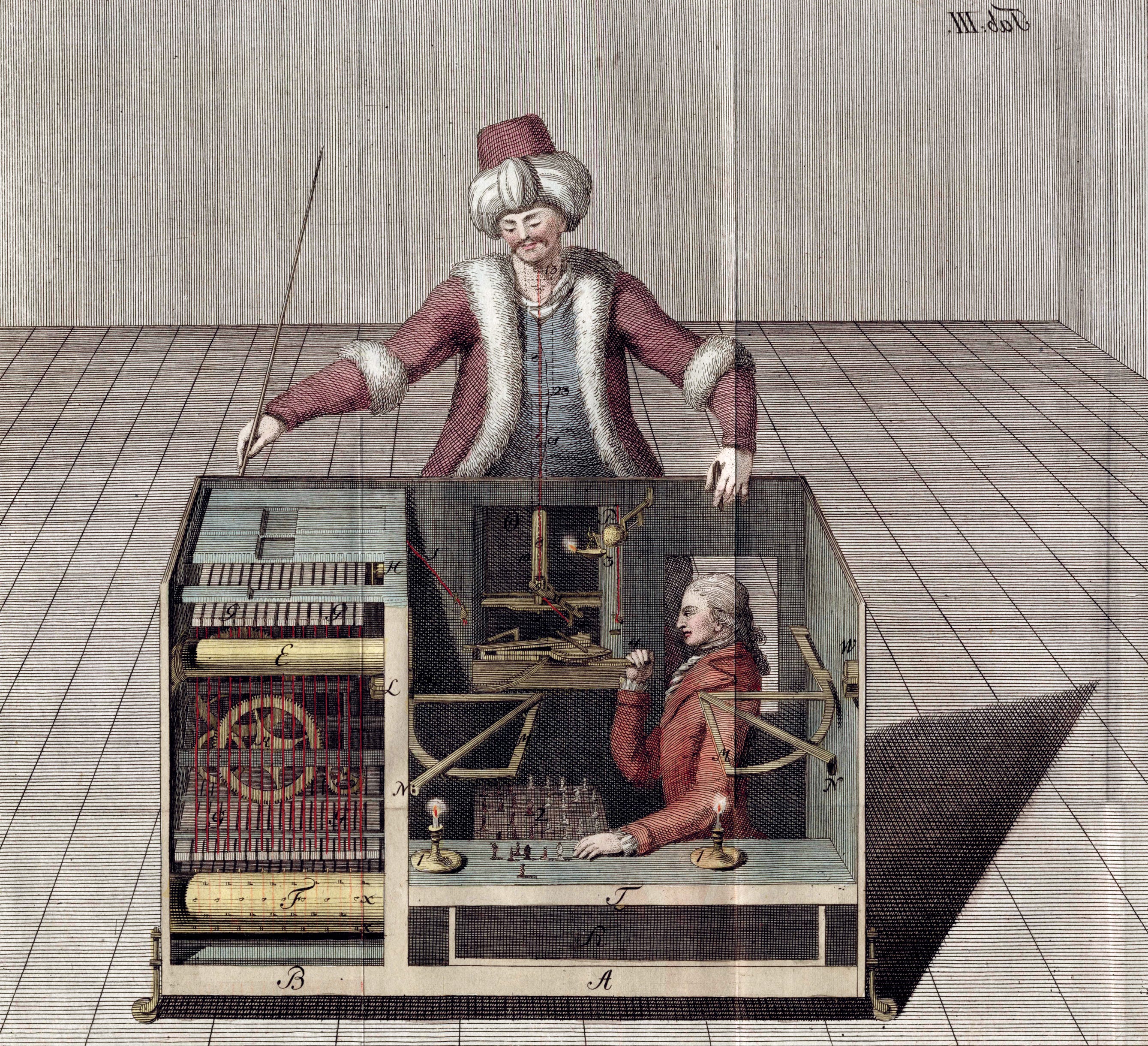

We would like to show, precisely, that the robot does not exist, that it is not a machine, no more so than a statue is a living being, but that it is merely a product of the imagination and of fictitious fabrication, of the art of illusion. The notion of the machine as it currently exists in culture, however, incorporates to a great extent this mythical representation of the robot. An educated man would neverdare to speak of objects or figures painted on a canvas as genuine realities, having interiority, good or ill will. However, this same man speaks of machines as threatening man, as if he attributed a soul and a separate, autonomous existence to them, conferring on them the use of sentiment and intention toward man.

– Gilbert Simondon, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects (p11), 1958.

This exposes also that culture has two contradictory attitudes toward technical objects. On one hand, Simondon argues, we threat technical objects as pure assemblages of matter with a mere utility, and in the other hand it also supposes that these objects are also robots and “that they are animated by hostile intentions toward man, or that they represent a permanent danger of aggression and insurrection against him.”. Simondon attributes this contradiction to a very interesting fact, that has roots in automatism concepts for it considers the level of perfection of a machine as proportional to its degree of automatism. Simondon argues that automatism is, however, a low degree of technical perfection because when you make a machine automatic you are also sacrificing a wide range of possible usages. Now, the interesting aspect is that what we actually see when the degree of technicity is raised on machines, it doesn’t correspond to higher levels of automatism but to a certain margin of indeterminacy and this margin is what allows the machine to be sensitive to outside information. Simondon says that “(…) a purely automatic machine completely closed in on itself in a predetermined way of operating would only be capable of yielding perfunctory results.” and that a machine with a high degree of technicity is an open machine. You can make many links here with AI in regards to the level of indeterminacy.

From tool bearer to spectator

From the seventeenth century to the eighteenth century, there was a clear continuous pace of evolution of technical objects according to Simondon, where instruments and tools became better (he cites the example of the gears and screw threads being cut better in the eighteenth century than in the seventeenth century) and this gave the idea of continuity of progress. This evolution did not cause any upheaval, it improved fabrication processes without disruption and the craftsman was able to preserve the habitual method but now with better results, causing a sensation of optimism in progress without anxiety. But when the transformations provoking a break within the rhythms of everyday life appear, the situation changes. In the seventeenth century, when they exchanged their tools for new tools, whose manipulation was the same, they have the feeling of being more precise and skilful, but in the nineteenth century, where we started to witness the birth of the complete technical individuals (do not read “individual” here as a human individual, this we will discuss later, it comes from the “individuation” concept that is more nuanced, just to avoid thinking that Simondon is saying that technical objects are humans), the confusion sets in.

Simondon mentions that as long as when these individuals were merely replacing animals, like in the case of steam engine that did not replace humans, this perturbation wasn’t followed by frustration, but when the automatic weaving loom, forging press, etc, this is what workers destroy during riots, because they are their rivals as the machine is no longer just an engine, but a bearer of tools like humans were. Simondon explain this as below:

(…) From then on the most positive, most direct aspect, of the first notion of progress, is no longer experienced. The progress of the eighteenth century is a progress experienced by an individual through the force, speed, and precision of his gestures. The progress of the nineteenth century can no longer be experienced by the individual because it is no longer centralized with the individual as the center of command and perception in the adapted action. The individual becomes the mere spectator of the results of the functioning of the machines, or the one who is responsible for the organization of technical ensembles putting the machines to work.

– Gilbert Simondon, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects (p162-163), 1958.

The most important aspect that Simondon mentions in my point of view is that in the nineteenth century, man doesn’t experience the progress as a worker, he experiences it as an engineer or a user. Simondon also mentions that at the end of the first half of the 19th century, poets keenly felt progress to be the general march of humanity, with its “charge of risk and anxiety”, bearing something “triumphant and crepuscular“.

Alienation, not only from means of production

One interesting realization from Simondon is related to the alienation caused not only by changes in means of production. After the nineteenth century revolution, the production of alienation, as grasped by Marxism as having its root in the relation of the worker with the means of production (because now the mans are not their property anymore), according to Simondon, this doesn’t only derive from the relation of property or non-property between worker and the machine or instrument of work. Simondon says that there is a more profound relation:

(…) that of the continuity between the human individual and the technical individual, or of the discontinuity between these two beings. The reason why alienation arises is not solely because in the nineteenth century the human individual who works is no longer the owner of his means of production, whereas in the eighteenth century the craftsman was the owner of his instruments of production and of his tools. Alienation does indeed emerge the moment the worker is no longer the owner of his means of production, but it does not emerge solely because of this rupture in the link of property. It also emerges outside of all collective relation to the means of production, at the physiological and psychological level of the individual properly speaking. The alienation of man in relation to the machine does not only have a socio-economic sense; it also has a physio-psychological sense; the machine no longer prolongs the corporeal schema, neither for workers, nor for those who possess the machines.

– Gilbert Simondon, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects (p165), 1958.

What Simondon is saying here is that this alienation of capital is not alienation with respect to labor, but rather with respect to the technical object. What labor lacks is not what capital possesses, and what capital lacks is not what labor possesses, he says. I think that this same profound psychological nuance emerged recently in AI as well, it doesn’t matter if you are a big company that is developing technology or if you are a user of technology, the technical individual, as Simondon says, “… is not of the same era as the labor that enacts it and the capital that frames it”.

Technology and Artificial Intelligence are not just tools

Just like Heidegger in his “The Question Concerning Technology” (Die Frage nach der Technik), Simondon doesn’t see technology just as a tool or simply means to an end as it is seen today by some groups. Technology has always been target of philosophical reflection as an instrument, as an economic reality and utility and this misses its essence. Technical objects are much more complex than this instrumental reduction, and we need philosophical thought to understand its essence. In Simondon’s philosophy, he describes two important concepts: concretization and individuation. I will try to make a summary of them, but both concepts have a lot of nuances and there are entire articles just working on the exact definition of these concepts.

Concretization: concretization is about how technical objects evolve to become more integrated and self-coherent systems over time. Simondon often separate abstract and concrete technical objects, a concrete technical object is one where all its parts work together in mutual synergy, rather than just being assembled as separate components. He gives also the example of the combustion engines: early internal combustion engines had separate systems for cooling (radiator), power generation (engine block), and lubrication (oil system). Over time, these evolved so that components served multiple functions (e.g. cooling fins became structural elements, oil helped cool and lubricate, etc). The engine became more “concrete” as its parts developed multiple integrated functions rather than remaining separate abstract elements. Concretization can be seen as a specific mode of evolution of technical objects. One important aspect here as well is that this process represents the technical and functional maturation of an object, where it increasingly resembles a natural system by being self-sustaining and autonomous. We will talk more about this later, on how technical objects doesn’t have to be seen as opposite to nature and how nuanced the notion of artificiality can be.

Individuation: describes the process by which entities (not only technical, but also biological) come into being as unique, coherent individuals within their associated milieu/environment. It is a dynamic process that involves the resolution of tensions or potentials between the entity and its environment. Note that in the Simondon’s individuation concept, this is always a on-going process, it is never complete, beings are always in a process of becoming. Individuation is also always relational, technical object achieves individuation when they establish a reciprocal relationship with its environment (e.g. as a turbine operating efficiently within a water flow system).

Now, I think the main revolutionary aspect of the Simondon’s philosophy is that these concepts bridge the technical-natural worlds. Both natural and technical objects go under the same similar processes of development and this makes the usual separation between “natural” and “artificial” much more blurry. Rather than opposing nature and technology, we can start to see that technology is an extension of nature, it is the extension of the human agency in nature, but not only that, these technical objects co-exist and co-evolve with us, they shape the way we see and interact with the nature and also change our culture and this is for me the most important point on why they are not just tools, they are mediators of our interaction with nature, and this mediation is not passive as it is actively influencing both the natural world and human culture.

When we start to understand technical objects through the lens of individuation and concretization, it is clear that Machine Learning/AI are not just a tool or a collection of tools with some utility or simply means to an end, they are part of our relationship with the world and have their own mode of existence that co-evolve together and change our culture. AI is shaping our future culture, society and our cognition, we cannot reduce it as simply tools of the human will.

Small detour: concretization makes inductive study sensible

Another very interesting part of the Simondon’s book in the chapter “The process of concretization” is when Simondon talks about the concretization and inductive study. He says that technical concretization makes primitively artificial objects increasingly similar to natural objects. The consequences of this concretization are not only human and economical but also intellectual:

(…) since the mode of existence of the concretized technical object is analogous to that of natural spontaneously produced objects, one can legitimately consider them as one would natural objects; in other words, one can submit them to inductive study. They are no longer mere applications of certain prior scientific principles. By existing, they prove the viability and stability of a certain structure that has the same status as a natural structure, even if it might be schematically different from all natural structures. The study of the functioning of concrete technical objects bears scientific value, since its objects are not deduced from a single principle; they are testimony to a certain mode of functioning and compatibility that exists in fact and has been built before having been planned: this compatibility was not contained in each of the separate scientific principles that served to build the object; it was discovered empirically; one can work backward from the acknowledgement of this compatibility to the separate sciences in order to pose the problem of the correlation of their principles and ground a science of correlations and transformations that would be a general technology or mechanology.

This is for me a very enlightening and it is precisely why there is scientific value in inspecting and understanding deep neural networks. For example, even though we know that LLMs have very different structures than biological structures, these objects were not deduced from a single principle and we can legitimately consider them as one would consider natural objects and submit then to inductive study as we do today.

Nuances of artificiality in Simondon’s integrated view

The widely understood meaning of “artificial” often refers to something that is man-made, unnatural, or opposed to the natural world. In Simondon’s philosophy, he offers a more integrated and dynamic perspective on artificiality. Simondon does not view artificial objects as fundamentally opposed to nature. Instead, he sees technology and artificial creations as extensions of natural processes. For him, technical objects are products of human creativity, which itself is part of nature. For Simondon, artificiality can be seen as a stage in the evolution of technical objects. As we mentioned before, an “abstract” technical object might seem artificial because it has not yet undergone concretization, so it is not well integrated in its milieu (environment). As these technical objects evolve and adapt, their artificiality diminishes, as they become more aligned with natural principles and better integrated into human and environmental systems. There is a very interesting example about the double flower in Simondon’s book:

(…) Artificiality is not a characteristic denoting the fabricated origin of the object in opposition to spontaneous production in nature: artificiality is that which is internal to man’s artificializing action, whether this action intervenes on a natural object or on an entirely fabricated one; a flower, grown in a greenhouse, which yields only petals (a double flower) without being able to engender fruit, is the flower of an artificialized plant: man diverted the functions of this plant from their coherent fulfillment, to such an extent that it can no longer reproduce except through procedures such as grafting, requiring human intervention. Rendering a natural object artificial leads to the opposite results to that of technical concretization: the artificialized plant can only exist in a laboratory for plants, the greenhouse, with its complex system of thermal and hydraulic regulations. (…)

Conversely, technical concretization makes the primitively artificial object increasingly similar to a natural object. (…)– Gilbert Simondon, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects (p57), 1958.

As you can see, his notion of artificiality is not rooted in the fabrication origin of an object. Artificiality can also be understood in terms of the alienation between humans and technical objects. When technology is poorly understood or remains “opaque”, it can seem foreign, unnatural, or even threatening. Simondon says that this perception of artificiality arises from a cultural failure to understand the internal logic and evolution of technical objects, rather than from any intrinsic quality of the objects. For Simondon, this dichotomy (of seeing technical objects as unnatural or artificial) is misleading because technical objects emerge from natural processes through human creativity, so technical objects are not an “other” to nature but a continuation of it through human agency. Please do not confuse that Simondon is saying that technical objects are natural living beings, Simondon is very clear on differentiation of its fundamental modes of individuation and relationship to the environment. What is important to understand here is its continuity, just as living beings evolve over time, technical objects undergo an evolutionary process through human innovation and the lines between the artificial and the natural and much more blurry than our current culture understands today.

The pedagogical proposal to technological literacy

What Simondon proposes to address the problem of alienation, when seen as arising mainly from the lack of knowledge of the mode of existence of technical objects and also how they evolve, is the reintegration of technology in culture and education. The cultural fear or rejection of technology arises often from a misunderstanding of the nature of technical objects and their role in our human life. Simondon argues that technology is not something alien or opposed to humanity, it is an extension of human creativity and a natural product of human activity.

Humans and technology are part of a co-evolutionary process where both influence and shape one another. Worrying about technology, as an example in “taking jobs” overlooks this broader interdependence. Jobs displaced by technology are not the destruction of human purpose but the transformation of human activity. Instead of fearing job displacement, society should focus on reorganizing and redefining work in ways that allow humans to collaborate with machines to create new opportunities.

It is clear that just reskilling is probably not enough for the next years and there will be a lot of challenges arising from AI, but I think that as a Machine Learning community we are not doing enough in terms of education of the public towards technology, which is the only way that people would have to understand what can happen to their careers in the future and how they can adapt, without an in-depth understanding of technology, the public is left at the hand of disinformation and our polarized cultural legacy.

Hope you enjoyed these notes as I enjoyed writing and reading Simondon’s work, I think it is an essential philosophy for the next decades to come.

– Christian S. Perone

Updates

03/Feb 2025: thanks Pablo Borba for catching some errors.

Your point about the cultural alienation from technology really resonates today, especially with AI. How do you think Simondon’s ideas could help society navigate the fear of automation replacing jobs?

Very good post and a reminder about some great philosophers. Heidegger is indeed also key in this question of alienation. If you find a copy of Michel Serres “The Natural Contract”, it will be quite insightful as a complement to Simondon. Thanks for taking the time to enlighten the “poor” mortals on this earth. Philippe (Belgian speaking D, F, NL and EN, living in Germany). PD: The website below is not maintained since more than 10 years.

Thank you for bringing light to Simondon’s work. As you say it is extraordinary that he is not more recognised.