Generalisation, Kant’s schematism and Borges’ Funes el memorioso – Part I

Introduction

One of the most interesting, but also obscure and difficult parts of Kant’s critique is schematism. Every time I reflect on generalisation in Machine Learning and how concepts should be grounded, it always leads to the same central problem of schematism. Friedrich H. Jacobi said that schematism was “the most wonderful and most mysterious of all unfathomable mysteries and wonders …” [1], and Schopenhauer also said that it was “famous for its profound darkness, because nobody has yet been able to make sense of it” [1].

It is very rewarding, however, to realize that it is impossible to read Kant without relating much of his revolutionary philosophy to the difficult problems we are facing (and had always been) in AI, especially regarding generalisation. The first edition of the Critique of Pure Reason (CPR) was published more than 240 years ago, therefore historical context is often required to understand Kant’s writing, and to make things worse there is a lot of debate and lack of consensus among Kant’s scholars, however, even with these difficulties, it is still one of the most relevant and worth reading works of philosophy today.

I’m perplexed that there are only sparse works about Kant’s philosophy in the ML community that are not related to ethics. Don’t get me wrong, ethics is as important as it ever was, but it won’t solve the riddle of generalisation. There is much more than ethics in philosophy.

In this article, I will do my best to show how Kant is very relevant to Machine Learning while avoiding doing exegesis of the CPR, however, I will leave a lot of references if you are interested in dedicating (which I hope you will) some more time to read. I think that as a Machine Learning community, we really need to pay more attention to philosophy. Neuroscience definitely has its place, but we need to remember that the brain is an organic solution to a problem, while the mind is a general solution, we cannot get distracted by looking at only one aspect of intelligence alone and keep doing correlation of embeddings with brain activity to argue we are in the right direction.

Situating schematism in Kant

I won’t go through the entire CPR here, there are many texts helping to understand it, one very good introduction to it is the Routledge Philosophy Guidebook by Sebastian Gardner [2], which is a fine introduction and companion to read the CPR. I will try, however, to explain what is required to understand and appreciate Kant’s ideas, but I will of course take shortcuts for that. I’m no Kant expert, I just love his writings and I think there is still much we can learn from.

The first thing you need to understand is that for Kant, there are forms of thought which cannot be learned or derived by looking at the world, these are the “categories” or “pure concepts of understanding”. This can become clear with the example [3] of a billiard table with one red billiard ball on it. Our understanding of the concept “red” comes from seeing things that are red that have similar attributes to it. However, we cannot learn about “oneness” by looking at the world, because we cannot learn the notion of oneness by looking at a lot of single things, this is presupposing the exact concept we’re expecting to learn and we are guilty of circularity.

Kant lists twelve categories, and then in the transcendental deduction chapter of the CPR, he proceeds by showing that these pure concepts of understanding are prerequisites to any empirical perception. In order to connect these abstract categories with the empirical world, Kant introduced the concept of schematism. Schematism is the process that mediates between pure, a priori concepts (the categories) and the sensory, empirical data we encounter. Without this intermediary step, the categories remain empty, and sensory data remains unordered. This mediation is crucial as it operationalises how abstract concepts apply to concrete experiences.

Kant posits that for each category there exists a corresponding “schema” or procedural rule that bridges the gap between the category and the sensory information. For example, the category of causality is tied to a schema that dictates how we perceive sequences of events and infer cause and effect. Without such schemata, abstract categories would have no way to manifest in any recognisable way in our perception and experience of the empirical world.

According to Kant, a schema is a “representation of a universal procedure of imagination in making an image for a concept” [1]. Kant thinks that no particular image of a triangle can be adequate to the general concept of a triangle, hence the need for the schematism and the “homogeneity” between what is intuited by sensibility and the concepts of the understanding. One thing that is very interesting here is that Kant attributes this procedure to imagination and it is impossible not to link imagination with generative models. It seems still not clear to me (and to many others as I can tell), however, how Kant envisioned this role of imagination into being able to go from concept to particular experiences, from general to particular. Even though we can imagine all sorts of triangles by knowing the concept of a triangle, it doesn’t seem possible that we are conceiving all possible triangles to “match” a particular triangle (although some authors proposed this explanation to schematism).

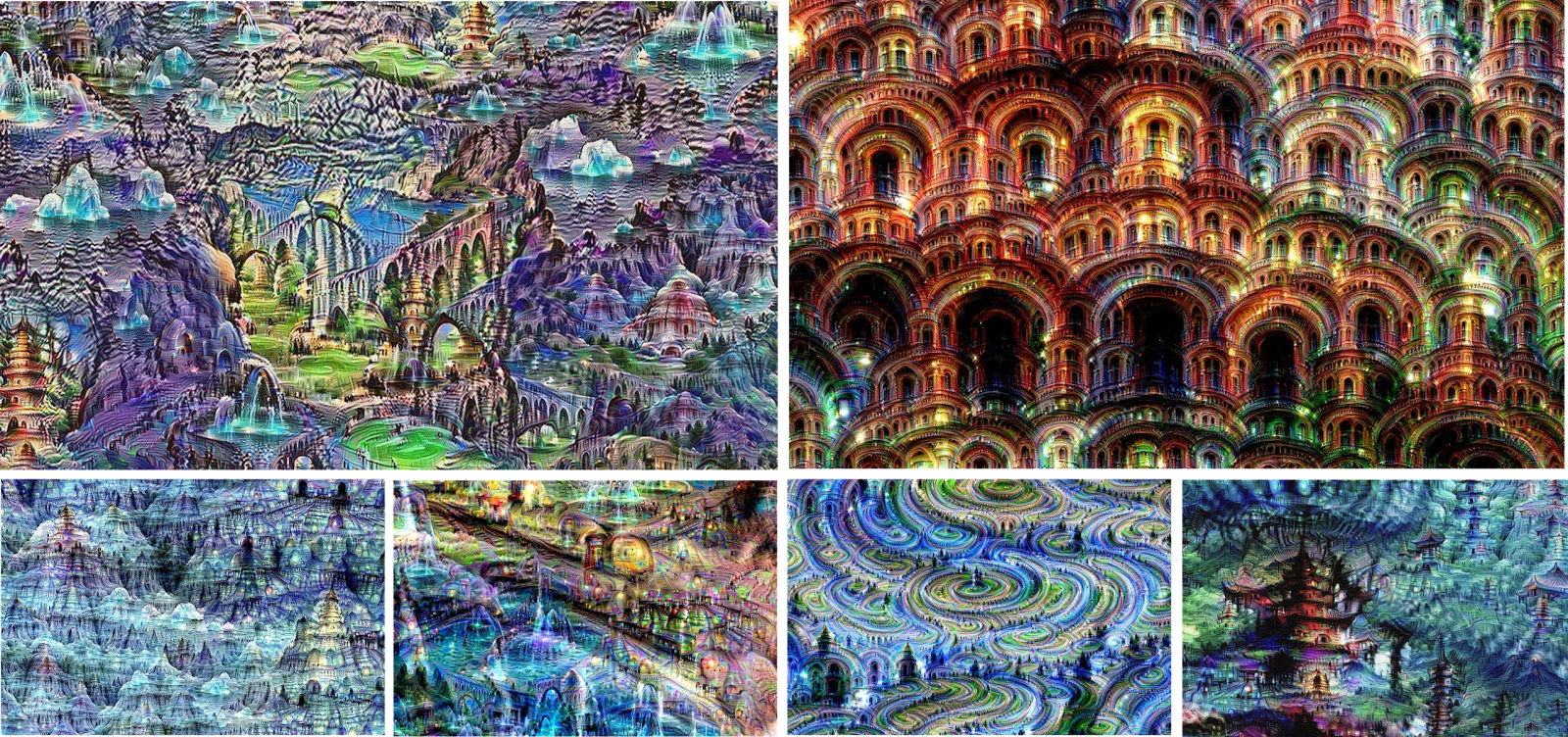

A coincidental connection with DeepDreams (or inceptionism)

There is a very nice paper [4] from Jessica J. Williams with the title “The Shape of a Four-Footed Animal in General”: Kant on Empirical Schemata and the System of Nature, where the author backs the argument with a lot of historical references that Kant had in mind scientific illustrations in his discussions of empirical images in the schematism chapter. The author cites the example of the Renaissance physician and naturalist Leonhart Fuchs who developed a new kind of scientific realism that focused on depicting the essential characteristics of specimens. The author in [4] describes a clear example: images of plants as simultaneously bearing fruits and flowers. These images were not naturalistically realistic, but were much more informative and besides being images (individual intuitive representations), they were used to communicate general information.

One very interesting connection of this idea of conveying information about a concept, in the same way as depicting images of plants simultaneously bearing fruits and flowers, is when we look at the (now old technique) of inceptionism (or DeepDreams) from Google in 2015, which I experimented with in 2015 as well after it was released with some images from Codex Seraphinianus. In inceptionism you basically invert the optimization goal, you can start with pure noise or with an existing image and then you do gradient ascent to maximize a particular layers activations. As you can see in the images, it is hard not see that what is happening here is the same as in the scientific illustrations mentioned by the authors of [4] where we don’t have naturalistically realistic images but we have a lot of information (as much as it is possible through optimization constraints and image contraints) about the concept of what is a building, what is a dog, etc.

To be continued

I found these ideas quite interesting, and there are a lot of interesting questions on the table right now, as we don’t really know how generalization works. What is the link of imagination with generalisation and the mediation of concepts and experiences ? What is the connection of generative models to schematism ? I believe that solving the riddle of Kant’s schematism is deeply tied to generalisation. Kant, however, left us in a very difficult situation (even to understand his solution to the problem).

To be continued in Part II once I get more time 🙂